It didn’t start with Tiger

By Don Kuehn,

CLG Board of Directors

If your exposure to minority participation in golf starts with Tiger Woods winning the Masters by nine shots in 1997 you’ve missed a great deal. Maybe you go back further, to names like Calvin Peete or Lee Elder (the first Black golfer to play in the Masters). You’re still not back far enough.

Ever heard of Charlie Sifford? He was the first Black player to break through the PGA’s “Caucasians only” clause and actually tee it up in Tour events on a regular basis. He made the way for guys like Jim Dent and Peete and Elder to join him on Tour.

It was through the caddie yard that most Black kids got their first taste of the game. Working long, hot days and playing on those days when the courses were closed (usually on Mondays), with whatever broken or discarded clubs one could find, is no way to hone a game. But many persisted and many excelled, only to be stymied by Jim Crow and “Caucasians only” rules of the day.

The fact that their place in history has not been adequately recognized should take nothing from the importance of those African-American golfers who persevered and persisted in pursuit of the game we all love (and alternately hate).

The reason for this article is not to recount the entire history of the Black experience in the game of golf. There are plenty of resources one can turn to for in-depth reflections and recaps of that topic. The point is to shed a little light on a few under-appreciated milestones that have seasoned the gumbo that is golf in America.

In 1896 the fledgling USGA held its second “Open” championship at Shinnecock Hills Golf Club on Long Island. It followed by just a day or two of the playing of the (more prestigious) US Amateur over the same course. Since golf was just a recent import to these shores, many of the participants were foreign-born — and white — save two: John Shippen and Oscar Bunn.

Over the protestations of many of the foreign-born who threatened to pull out of the tournament if these two were allowed to play, USGA President Theodore Havermeyer (yeah, the guy whose name is on the big trophy) stood his ground and allowed the two to play. To the surprise of many, including the renowned Charles Blair MacDonald who withdrew after the first day, Shippen tied for the lead after the first of two rounds. His fate was sealed, however, at the relatively easy par-four 13th hole on the second day where he took an unlikely 11 and finished the event in a tie for 5th place.

Shippen, it is believed, was not just the first Black player to compete in an Open, he was the first American-born golfer of any race to turn professional.

If you’re interested in pursuing this topic, I recommend two very good books that take on the Black golf experience in-depth: A Course Of Their Own by John H. Kennedy and Uneven Lies, by Pete McDaniel. In those works, you’ll find tales of indignity, intolerance, and injustice that we’d probably wish were not part of the great game that binds us together. You’ll read about Bill Spiller, Teddy Rhodes, Elder, Peete, Sifford, and others. You’ll get to understand the role heavyweight champion Joe Louis had on Black golfers in the United Negro Golfers Association, the Negro National Open, and more. Black golf, not unlike the Negro Leagues in baseball had a social and cultural fabric that was woven in tough times, glad times, and struggles.

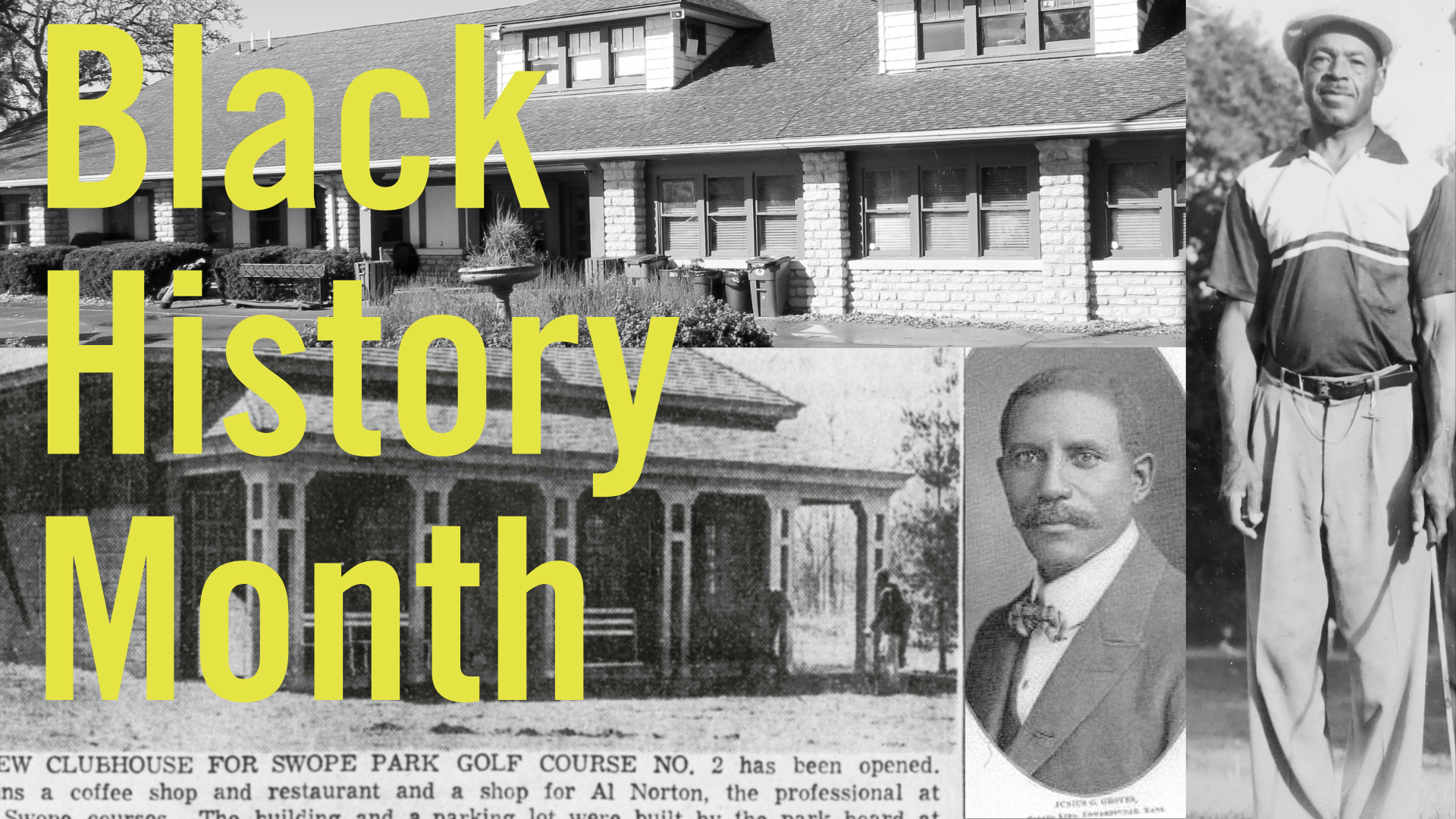

But what about here in the Midwest? Well, In 1879 a freed slave by the name of Junius Groves walked from Kentucky to Kansas City. When he got here he had virtually no money, but he found work as a sharecropper, eventually, he did save some money, bought a little land, and started growing potatoes.

By the early 1900s, he was so successful he became known as “The Potato King of the World.” He was so good at what he did, a small town grew up around his operation between Edwardsville and Bonner Springs. It was called Groves Center.

So, I guess you’re asking yourself: what do potatoes have to do with golf?

Well, I’ll tell you. Groves built a small golf course on some of his property just for the use of his Black employees. I doubt there was any other “exclusively-Black” golf course anywhere else in the country at the time… that is, not on purpose, anyway.

So, from the dirt and dust and sand greens of the potato farm, came a group of players who eventually morphed into the Heart of America Golf Club. The HOAGC became the organization for minority golfers in this area.

In 1938 they sued the city and its Parks Board for the right of its members to play on the course that they were, in fact, paying for through their taxes: Swope #1. Times were changing.

A few years later the US entered World War II. Thousands of Black men enlisted in the armed services. Thousands of Black women worked in war industries.

In 1948 President Harry Truman issued Executive Order #9981 which abolished racial discrimination in the armed forces. Although effectuating the president’s order would take years, it proved to be the first bullet fired at “Jim Crow” in the military.

So, eventually, veterans came home and tried to rebuild their lives. But on the streets of Kansas City, like the rest of the country, it wasn’t so easy…

>> Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey would be the ones to break the color barrier in the major leagues (though that wouldn’t be complete for another decade).

>> Dr. Martin Luther King’s first application of non-violent protest was still years away.

>> Brown v. Board of Education was not on the radar yet.

>> Ms. Rosa Parks wouldn’t take her stand on the Montgomery bus for another five years.

But golf was becoming one of the first battlegrounds in the fight for civil rights, not just here, but around the country.

African-Americans fought for freedom in Europe and Asia but found little of it when they came home. The right to vote, to have access to good schools, to eat in restaurants, and shop in stores of their choosing was denied to them.

In golf, Kansas City’s Swope #1 was like a virtual country club for middle-class whites. The A.W. Tillinghast design was about as closed to the non-white public as the most exclusive clubs in town.

Black golfers had access to that nine hardscrabble holes at Swope #2, but… only on Mondays and Tuesdays.

Well, on March 24, 1950 the President of the HOAGC, Mr. George Johnson – who started playing on that potato farm back in the ’20s – and three of his buddies:

Mr. Reuben Benton, a newspaperman who later became co-owner of The Call newspaper,

Mr. Sylvester “Pat” Johnson, and Mr. Leroy Doty — who were also part of the Heart of America Golf Club — climbed the steepest hill in local golf: They drove up to Swope #1 and forced the issue.

According to an article written by J. Brady McCollough for the Kansas City Star in 2005,

They drove that winding road up the hill, walked into the clubhouse, and laid their greens fees on the counter. The man behind the counter looked up, astonished. They knew what he would say.

‘You can’t play here, but you can play at course #2.’

He expected them to walk away and get back into their cars like the Black men who preceded them. But not on this day. Not with the seeds of change that had been planted across the country.

They went to the first tee and hit their drives under the glare of the superintendent. Beaten, he walked back to the clubhouse.

Meanwhile, anticipating the sounds of sirens and police that never came, the four men enjoyed what would be the first of many rounds on the hallowed grounds of Swope #1.

Eventually, the city stopped maintaining the Tillinghast course as fewer and fewer white players showed up. The period of decline lasted almost 25 years. Not until Mr. Ollie Gates, an old friend of Reuben Benton’s and head of the Parks Board, pushed for the city to back the renovation of Swope to its pre-1950s splendor did it become everybody’s golf course again.

In 2014 the Kansas City Golf Hall of Fame inducted those four gentlemen, Johnson, Benton, Doty, and Johnson, known as “The Foursome,” into the Hall for their courageous stand against the Jim Crow laws of the time.

But the Swope episode opened the door to a number of quality Black players who came later. Tommy Williams was as good as any around here, Bill “Turk” Redmond had game, and Tom Rhone not only played and played well, he was an early leader in the First Tee program here, in Kansas City.

Over the past few years, Chris Harris has taken steps to not only improve his neighborhood, but he has built a sports complex around 40th and Wayne that includes a golf course, basketball, and volleyball courts. Harris’s goal is to provide urban kids with activities that foster sportsmanship, honor, and discipline which he believes are “skills needed to thrive in the growing and ever-changing world in which we live.”

John Shippen, Tommy Williams, Chris Harris… just a few names that deserve some recognition during this Black History Month. It didn’t start with Tiger.

# # #