The Kansas City Golf Hall of Fame will add four new members to its ranks at a luncheon and induction ceremony at Milburn Golf and Country Club on November 23, 2024, beginning at 12:00 PM.

This year’s class will include long-time Head Professional at Mission Hills Country Club, Charles Lewis III; Marty Sallaz, one of only a handful of golfers to have won both the Kansas and Missouri Amateurs; PGA Tour professional Tom Pernice Jr. who got his start as a young golfer here, in the Kansas City area; and Carolyn Lee, a “Committee Selection” who won the very first two Kansas City Women’s Championships in 1915 and ’16 and three consecutive Missouri Women’s Amateurs from 1918 to 1920.

A closer look at this year’s honorees:

Charles Lewis III is the son and grandson of golf professionals who served the members of Mission Hills Country Club for thirty years. He had a good amateur career before his big “claim to fame” at the 1960 US Amateur in St. Louis. There, after advancing to match play and knocking off his first three opponents, he faced the defending champion, a pudgy kid from Columbus Ohio named Jack Nicklaus.

Golf World magazine called Lewis’ take-down of the champion “the greatest match play upset of the 20th century.” His march to the semi-finals that year guaranteed him a spot in the 1961 Masters Tournament.

After serving in the Marine Corps and trying the professional tour for a time, Lewis worked as Assistant to “Duke” Gibson (Hall of Fame class of 2013) at Blue Hills before accepting the Head Professional position at Mission Hills in 1975.

Marty Sallaz was a mainstay on the local golf scene for many years. Among his championship titles are the 1990 Missouri Amateur, the Missouri Fourball and the Dawson and Phil Cotton titles.

He reached the final match in the Kansas Amateur four times, winning it all in 1995 and collecting four Kansas Mid-Amateur titles between 1992 and 2000. He also represented Kansas in the USGA State Team Championship in 1995 and 1999.

Tom Pernice Jr. graduated from Raytown High School where he captured All-state honors before moving on to play at UCLA. He was two-time All-American and PAC 10 Player-of-the-Year on a team that featured four other players who would go on to win on the PGA Tour.

Locally he won the Heart of America Four Ball, was runner-up in the Missouri Amateur and qualified for 6 USGA championships. As a professional, he won the Midwest Section PGA Championship three consecutive years (1984 -’86).

On tour, he won twice, made an impressive 317 cuts and earned over $15 million in prize money. After turning 50 he joined the PGA Tour Champions where he won six titles, including the season-ending Charls Schwab Championship in 2014. Pernice has played in twenty-seven of golf’s “Majors”.

Carolyn Lee won the first two Kansas City Women’s Championships at a time when clubs were hickory shafted, balls were made with Balata rubber and many courses still had sand greens. Originally from the old Evanston Golf Club, then from Hillcrest, Ms. Lee dominated local tournament golf in the early 1910’s and into the ‘20’s. She won three consecutive Missouri Women’s Championships from 1918 to 1920 and won the old Tri-State and Missouri Valley titles as well. Her record in the Missouri Women’s Amateur was a staggering 26-3.

Ms. Lee enters the Hall of Fame as a Committee Selection.

“The Hall of Fame was created in 2012 as part of our celebration of the centennial of the KCGA,” said Doug Habel, Executive Director of Central Links Golf (CLG). “Our goal is to preserve our past and honor the accomplishments and contributions of those who made golf in this area great. Central Links Golf is committed to continuing the tradition established prior to the merger of the KCGA and the Kansas Golf Association.”

“Over the first five classes of inductees,” he said, “we have recognized amateurs and professionals, men and women, contemporary as well as historic figures, golf administrators and superintendents and players and teachers. We are very proud that our Hall of Fame is all-inclusive and has recognized the greatest of those who have contributed so much to the enjoyment of our game.”

Previous inductees in the class of 2013 included professionals Tom Watson, Stan Thirsk, Leland “Duke” Gibson; 1927 US Women’s Amateur Champion Miriam Burns (Horn) Tyson; founding member of the LPGA Opal Hill; long time KCGA Executive Director Bob Reid; and pioneering course superintendent Chester “Chet” Mendenhall.

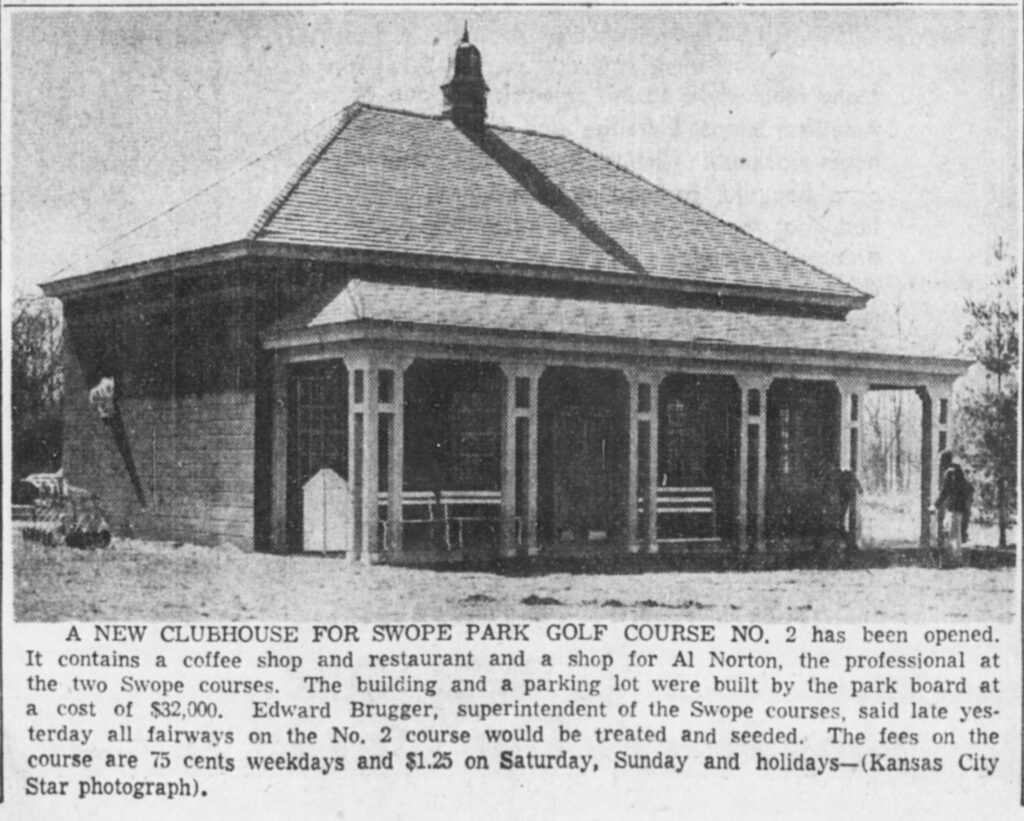

In 2014 the honorees were teaching and touring professional Bob Stone; amateur stand-out Karen (Shull) MacGee; and “The Foursome” a group of African Americans who integrated the links at Swope Park in March 1950.

The 2016 class recognized “The Father of Kansas City Golf” James Dalgleish; amateur player Marian Gault; and Bill Ludwig, long-time Board member, volunteer and champion player.

The 2018 class brought touring professional and outstanding amateur Jim Colbert; Jean Pepper who was the “player to beat” in the 1930’s and 40’S; Frank Kirk who was instrumental in the establishment of the First Tee program and has served on the Boards of various golf organizations; and Maxine Johnson who dominated women’s golf in the 1950 in the region.

In 2020 the class included amateur Steve Groom; long-time professional Rob Wilkin; the late Dave Fearis, who was Superintendent at Blue Hills for 40 years; and Mary Jane Barnes, the first woman to head the KCGA and 18-time Women’s club champion at Kansas City Country Club.

The class of 2022 featured the Devers Family: Maxine, Andy, Ian and Clay who all were champion golfers in their day; Fred Rowland, winner of the Canadian Senior Amateur, nine Kansas Championships, seven Kansas City titles and qualified for 11 USGA championships; and Don Kuehn, who has won over 50 championships in local, state and national tournaments.

Nominees are voted on by a broad cross-section of local electors: all members of the CLG Board, living members of the Hall of Fame, the Executive Board of the Midwest Section PGA, representatives of the Golf Course Superintendents Association and emeritus members of the CLG Board. Five nominees appeared on this year’s ballot and each voter was able to cast three votes.

The induction will take place at Milburn Golf and Country Club at 12:30 PM on Saturday, November 23.

The public and the media are welcome and encouraged to attend.

# # #

For more information, please contact:

Doug Habel

Executive Director

Central Links Golf

(913) 649-5242

doug@clgolf.org